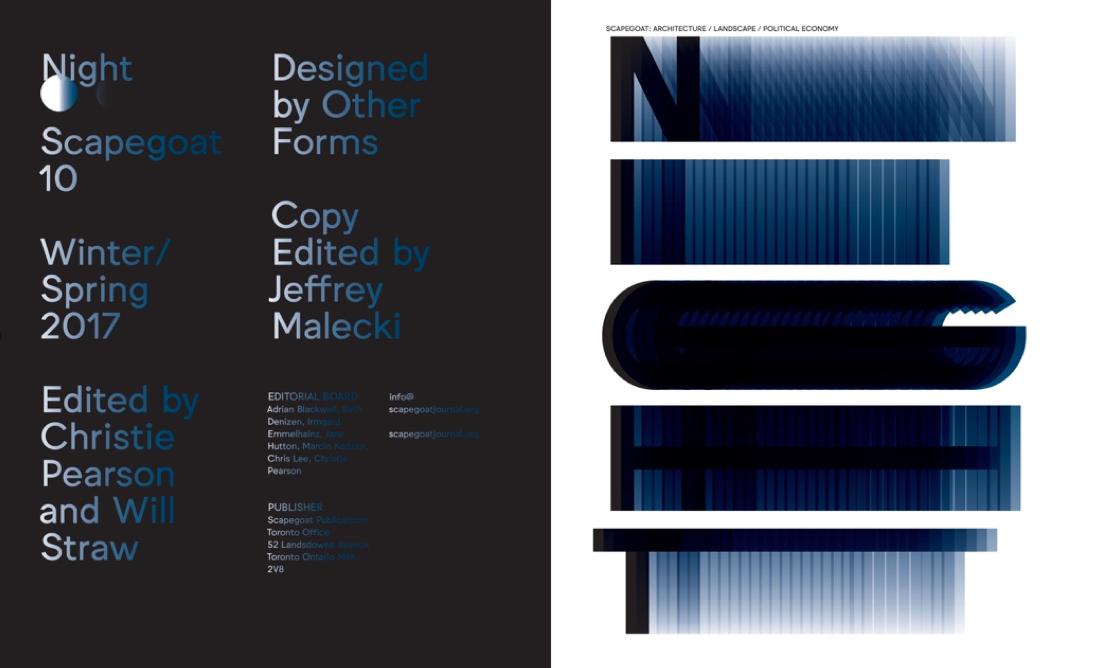

2017

Concept and Issue Editors: Christie Pearson and Will Straw

Scapegoat journal is free to read and order here.

NIGHT drags architecture and landscape into the realm of temporality. The hidden, illicit, clandestine, lunatic, and aquatic are folded into the night. How can we “take back the night” while tending its oceanic depths? What tools do we need to counter the exploitation of the night as real estate? We watch the management of night, as an object of investment, growing, see it increasingly understood as a site of production and a horizon of consumption. What remains for the dreamer when night is pulled into the light of day? Contemporary debates about the urban night, from dark sky movements to the call for fully illuminated cities of safe passage all serve to complicate each other.

NIGHT also invites us to jouissance, the French term used in the recently published Toward an Architecture of Enjoyment by Henri Lefebvre, who explores the painful lack of architectures created to produce pleasure, such as the bath house. In this issue we find additional nocturnal architectures as typologies of public pleasure, including Philippe Rahm’s night garden for humans and non-humans; Eleanora Diamanti, Leo Zhao, and Marie-Paule Macdonald’s nightclubs; Natlie Jachyra’s alleyways; Curt Gambetta’s empty buildings; and Peter Lamborn Wilson’s school of Nite, where mystery and desire reign.

The 24-hour cycle of day and night is marked, in geographer Luc Gwiazdzinski’s words, by a “discontinuous citizenship.” In the passage from day to night, the rights of women, racialized populations, youth, and the homeless wax and wane. One of the key new battlefronts in North American cities centres on the right to sleep at night outside of fixed addresses—on the sidewalk (in Kelowna, British Columbia) or in your car (Los Angeles). In gentrifying cities like Paris, the alcohol-centred economies and exclusions of the night are being pulled into the day, as café and bar owners expel the low-spending men of immigrant populations who traditionally gather until midday to drink coffee and converse.

At another economic scale, the protected “dark skies” of the US-Mexican border regions intensify panics of immigration, but are themselves threatened by the 24-hour spectacles of oil rigs and gas flares, which glow until plunging prices or resource exhaustion send them elsewhere (Mueller and Kripa). The authors of the 2014 São Paulo “Night Manifesto” asked whether the day should remember the night (Dietzsch). Should the day absorb the injuries and transgressions of the night, and make them its own? Or is the insidious work of the day, in every 24-hour cycle, to repair and contain the experiences of the night? Is the role of nighttime lighting to remember (and highlight) the power-architectures of the day, so that they do not disappear? Or should nocturnal illumination forget the daytime city, producing new versions of urban space with each setting of the sun?